The most frequent brain tumour in children is called a pilocytic astrocytoma, and it most frequently develops in the posterior fossa. Complete resection typically results in the patient's recovery; nevertheless, the...

Introduction

The most frequent brain tumour in children is called a pilocytic astrocytoma, and it most frequently develops in the posterior fossa. Complete resection typically results in the patient's recovery; nevertheless, the patient may also experience hydrocephalus and brainstem compression, both of which carry a risk of death. So, getting a diagnosis and starting therapy as soon as possible is crucial.

Younger patients are more likely to develop these low-grade, typically well-circumscribed tumours. They are grade I gliomas and have a fair prognosis according to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) classification of central nervous system tumours.

PCA most frequently happens in the cerebellum, but it can also happen in the brainstem, optic nerve, and hypothalamus. They can also happen in the cerebral hemispheres, albeit young adults are more likely to experience this. This article will solely cover PCA of the cerebellum because the presentation and therapy differ for PCA in different sites. Astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells, and microglia are all types of glial cells.

The most prevalent tumour of glial origin, astrocyte-derived tumours are those that develop from astrocytes. These tumours were categorised by the WHO in 2016 as "other astrocytic tumours" or "diffuse gliomas." Grade II and III diffuse astrocytomas, grade IV glioblastoma, and diffuse gliomas of infancy are all examples of diffuse gliomas. PCA, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, and anaplastic carcinoma are all included in the category of "other astrocytic tumours."

The grading scheme mentioned above is histological. It is important to note that while PCA is primarily a histology diagnosis, the 2016 WHO classification places more emphasis on genetic and molecular markers for classifying gliomas.

Etiology

- With up to 20% of NF1 patients developing a PCA, which most frequently affects the optic system, there is a clear correlation between NF1 and PCA. It is believed that rather than being inherited, the majority of PCAs are spontaneous mutations.

- In the vast majority of PCAs, changes to the BRAF gene and MAPK signalling pathway have been discovered. A mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK) pathway activator, BRAF is an intracellular serine/threonine kinase. Human malignancies have been identified to be brought on by mutations in the porto-oncogene BRAF.

Epidemiology

- The most frequent solid cancer in young people is brain tumours. With a frequency of 0.8 per 100,000 people, PCA is the most prevalent brain tumour in children. 75% of PCA cases begin before the age of 20, with the second decade of life being the most common time for onset. PCA makes up 27 to 40% of paediatric posterior fossa tumours and 15% of all brain tumours in children. Although they typically affect young persons, they can also affect adults.

- PCA makes for 5% of all primary brain tumours in adulthood; while they are still frequently detected in the cerebellum, one case series discovered that the temporal and parietal lobes are where they are most frequently found.

Pathophysiology

Although it might be more lateral in an adult, PCA often occurs in the cerebellum near to the midline. Anywhere inside the neuroaxis can experience PCAs:

- 42% to 60% of the cerebellum

- 9% to 30% for optic gliomas and hypothalamic gliomas The most frequent location for PCA involving NF1[5]

- 90% Brainstem

- 10% spinal cord

- Hemispheres of the brain (young adults).

Histopathology

PCA is a grade I tumour according to the WHO. Anaplastic PCA has case series with variable behaviour.

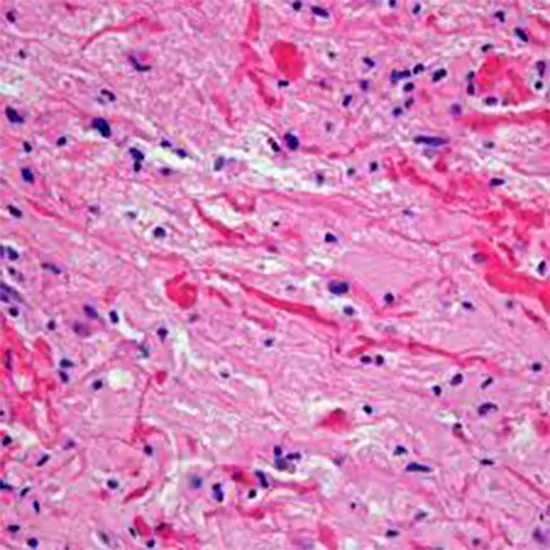

microscopic characteristics:

- The name PCA comes from the microscopic appearance of cells with long, thin bipolar processes that resemble hairs. (hence pilocytic). On hematoxylin and eosin staining, Rosenthal fibres, which are elongated eosinophilic bundles, are frequently present. Low to moderate levels of cellularity characterise PCAs. It is possible to find multi nucleated large cells with periphery nuclei.

- Long-lasting tumours may feature calcifications and hemosiderin-rich macrophages. Though extremely rare, areas of necrosis can be found.

- Despite being well-circumscribed in radiology, about two-thirds of them invade the parenchyma around the brain.

- PCA and low-grade diffuse astrocytoma might be difficult to distinguish from one another under the microscope.[2] For this reason, the pathology team requires access to demographic and radiographic data in order to aid in diagnosis. This diagnostic problem is also made worse by the few biopsy samples.

Molecular characteristics:

- In between 70% and 75% of PCAs, BRAF gene mutations are the most prevalent genetic aberration. Compared to adult PCA, BRAF mutations are more frequent in paediatric PCA. More than 80% of the time, PCAs result in changes to the MAPK signalling pathway.

- The most typical PCA mutation discovered is the KIAA1549-BRAF fusion. For glial fibrillary acidic protein, S100 protein, and oligodendrocyte transcription factor, immunohistochemistry results are positive. Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) and tumour protein p53 (TP53) mutations are not present in these children's low-grade gliomas, which is significant.

Symptoms

- The posterior fossa mass effect might cause PCA to exhibit secondary symptoms. This could involve obstructive hydrocephalus, which could lead to headache, nausea, and vomiting as well as papilledema. An increase in head circumference is likely to happen if hydrocephalus develops before the union of the cranial sutures (about 18 months of age).

- Peripheral ataxia, dysmetria, intention tremor, nystagmus, and dysarthria are symptoms of cerebellar hemisphere lesions. On the other hand, a broad-based gate, truncal ataxia, and titubation are brought on by lesions of the vermis. Cranial nerve palsies are another complication of posterior fossa lesions. Diplopia could be caused by abducens palsy from the nerve's stretching. Additionally, papilledema may cause them to have blurry vision. With posterior fossa lesions, seizures are uncommon.

Investigation

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast is the preferred research. Radiation exposure is also avoided in this way. However, an immediate head computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast is recommended if the kid is neurologically unstable. Children with posterior fossa tumours typically undergo full neuroaxis imaging in clinical settings because more aggressive tumour forms can generate drop-metastases. Since PCAs do not develop drop-metastases like ependymomas and medulloblastomas do, complete neuroaxis imaging is not necessarily necessary. It is significant to note that the variation pilomyxoid astrocytoma can generate drop-metastases and is more aggressive.

PCA can present in a variety of radiological ways. While the cyst wall also improves in 46% of cases, 66% of cases have a sizeable cystic component with an avidly enhancing mural nodule. The tumour is solid with little to no cystic component in up to 17% of instances. A calcification of up to 20% is possible. In 82% of cases, PCA occurs periventricular. Since the cyst material contains protein, it frequently has a higher density than the cerebrospinal fluid. (CSF) The mural nodule on an MRI scan appears hyper-intense on the T2 image but is iso or hypo-intense on the T1 image. Similar to the CSF, the cyst content exhibits a high signal on T2 imaging. To distinguish the nodule from low-grade gliomas, it is aggressively enhanced as previously mentioned.

Management/Treatment

Control of the Tumour

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, with the goal of attaining complete resection margins with the least amount of neurological damage. Complete resection is thought to be therapeutic for the condition. Complete excision, however, could not be possible if the brainstem or cranial nerves are affected. It is advised to only remove the nodule and not the cyst wall. However, tumours with a thick cyst wall can be removed because they are regarded as a component of the nodule.

Conventional radiation is not necessary; serial imaging follow-up is more suitable. Significant aftereffects of radiotherapy, particularly in this area of the brain, are present. Further surgical resection is often used if there is a recurrence. If a tumour cannot be removed surgically or if malignant histology is present, radiotherapy may be necessary. For persistent and recurring malignancies, stereotactic radio-surgery (SRS) has had excellent results in several studies. However, criticism of the length of follow-up in these studies has been raised. Some worry that SRS might promote anaplastic transition.

Treating hydrocephalus

Methods for Patients Who Are Neurologically Well:

- CSF diversion during surgery, followed by prompt tumour removal

without CSF diversion, surgical resection. CSF diversion should be used if:

- postoperative hydrocephalus remains.

- CSF diversion two weeks before the actual procedure.

Urgent intervention is required if the patient has hydrocephalus or brainstem compression and is neurologically unstable. Some writers recommend early CSF diversion with an external ventricular drain (EVD), endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV), or ventricular-peritoneal shunt before performing definitive surgery if the patient presents with hydrocephalus. (VPS). Some hospitals will implant an EVD or perform an ETV during surgery, followed by rapid removal of the tumour. Some, however, argue that CSF diversion should occur two weeks or so before resection.

This method is unpopular since installing a VPS typically subjects patients to problems and lifelong shunting. Additionally, although it is uncommon, tumour seeding into the peritoneum is possible. This risk can be reduced by mounting a tumour filter on the shunt system. Possible upward Tran stentorian herniation and CSF infection brought on by VPS or EVD contamination are surgical concerns to take into account with CSF diversion. Some critics claim that this approach delays decisive care needlessly.

Diagnosis

Paediatric Posterior Fossa Tumours That Are Most Common:

- Medulloblastoma (usually midline, fourth-floor vermin, 10% calcified)

- Pontine diffuse glioma (usually multiple cranial nerve palsies)

- Ependymoma (usually arise in the floor of the fourth ventricle, calcification common)

- Children's Posterior Fossa Lesions Other (clinical and radiological differentials)

- Hemangioblastoma

- Rhabdoid/atypical teratoid tumour

- a brain abscess

- Papilloma of the choroid plexus

- Neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilm's tumour metastatic diseases.

Adults Posterior Fossa Tumors (clinical and radiological differentials)

- Metastasis (by far the most common)

- Hemangioblastoma (7 to 12% of all posterior fossa lesions in adults, vascular, often cystic)

- Brainstem glioma

- Abscess

- Cavernous malformation

- Ischemic stroke

- Cerebellar haemorrhage

Prognosis

PCA is a slow-growing tumour that can frequently be successfully removed. Total resection is the greatest prognostic indicator. If entirely removed, the 10-year survival rate is roughly 95%. If total resection is accomplished, recurrence is uncommon. Those that do recur typically do so in a short period of time. According to Collins' Law, "the age of the child at diagnosis plus nine months is the period of risk for tumour recurrence."According to this theory, PCA is deemed to have been cured if it doesn't return within that time. There have been reported instances of late recurrence, nevertheless.

If the tumour has not been completely removed, it may return when the symptoms worsen. There are several known risk factors for recurrence, such as a solid tumour, exophytic component, and tumour invasion.

Complications

Patients who have tumours in the posterior fossa may experience hydrocephalus and need a VP-shunt. If so, they'll probably be permanently dependent on shunts. Even though recurrence is typically treatable with additional resection, a small percentage of PCAs exhibit malignant degeneration. The majority of cases of malignant degeneration appear to be treated by radiation.

Summary

The most typical paediatric brain tumour, PCA, should be treated urgently and is regarded as a chronic condition. Initially, these individuals will visit paediatricians, emergency room doctors, or general practitioners. These professionals must therefore be aware of the warning signs and symptoms of tumours affecting the cerebellum or brainstem, including the clinical presentation of hydrocephalus.

The decision-making process will be carried out by an inter-professional team that includes neurosurgeons, oncologists, radiologists, neurologists, and primary physicians. The preoperative team will be made up of primary doctors, neurosurgeons, anaesthetists, intense visits, and nursing teams. Physiotherapists will aid the patient with daily living activities during the postoperative and rehabilitation period.

For PCA, there are no reversible risk factors. Genetic testing and counselling may be necessary because some genetic disorders, such NF1, predispose families to PCA. But random mutations are what cause the majority of PCAs.