The widespread virus cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause severe end-organ dysfunction in immunocompromised patients with congenital CMV illness, or it might be asymptomatic in healthy individuals.

The widespread virus cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause severe end-organ dysfunction in immunocompromised patients with congenital CMV illness, or it might be asymptomatic in healthy individuals. The herpesvirus family, often known as the herpesviridae or human herpesvirus-5 (HHV-5), includes the human cytomegalovirus. Salivary glands and human cytomegalovirus infections are frequently linked. CMV infections may not cause symptoms in healthy individuals, but they can be fatal in immunocompromised patients.

Salivary glands and human cytomegalovirus infections are frequently linked. While CMV infection may not cause any symptoms in healthy individuals, it can be fatal in an immunocompromised patient. Congenital CMV infection can be fatal or cause serious illness. CMV frequently remains dormant after infection, although it could reactivate at any time. It eventually results in mucoepidermoid carcinoma and is thought to be the cause of prostate cancer.

In wealthy countries, the prevalence of adult CMV infection ranges from 60% to 70% to over 100% in impoverished countries. Of all the herpes viruses, CMV possesses the most genes devoted to evading the host's innate and adaptive protection. Lifelong effects of CMV include immune dysfunction and antigenic T-cell surveillance. Congenital CMV is the primary infectious cause of intellectual disability, learning difficulties, and deafness.

ETIOLOGY

The herpesvirus family includes CMV, a double-stranded DNA virus. After clearing the initial infection, CMV stays latent inside the host, just like other herpesviruses. Immune system impairment brought on by immunosuppression results in viral reactivation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

With a rise in seroprevalence with advancing age, the population's exposure to CMV affects about 59% of those older than six years old. A primary infection, a reinfection, or a reactivation can all result in infection. There are several other ways that CMV can be transmitted, chest x-ray including through blood products (transfusions, organ transplantation), breastfeeding, viral shedding in close-contact settings, perinatally, and sexually. Reactivation occurs in people who have immunosuppression and is linked to increased morbidity and death.

- Primary infection: an infection that can be asymptomatic in patients who are seronegative.

- Continued infection: CMV reactivation or reinfection in patients who are seropositive infection with CMV CMV contamination in tissues or bodily fluids (blood, urine)

- CMV infection with corresponding non-specific signs and symptoms and/or end-organ involvement is known as CMV illness.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The CMV virus remains dormant in myeloid cells after transmission and after the primary infection has cleared. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity has a major role in controlling vital replication and reactivation. The appearance of symptoms, primarily in immunocompromised patients, results from the release of virions into the circulation and other body fluids when reactivation happens.

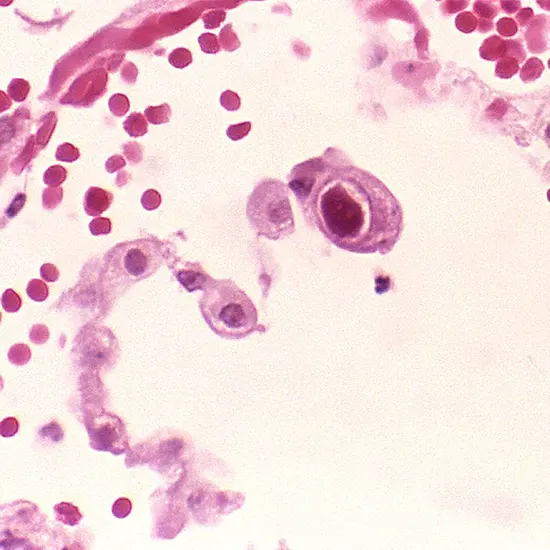

HISTOPATHOLOGY

- CMV replicates slowly inside endothelial cells. CMV expresses genes in a temporally controlled way, just like other herpesviruses.

- Transcription is regulated by early genes between 0 and 4 hours after infection.

- Early genes play a role in viral DNA replication and additional transcriptional regulation between 4 and 48 hours after infection.

- Late genes, which encode structural proteins, are expressed throughout the remaining stages of infection up until viral egress.

- While the virus uses the host's RNA polymerase to carry out the transcription of its genes, CMV encodes for a functional DNA polymerase.

- The viral double-stranded DNA genome is created in the nucleus of the host cell, specifically in compartments designed for viral replication.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The course of primary CMV infection is typically asymptomatic or subclinical. The most frequent form of CMV infection in people with a healthy immune system is mononucleosis, which is characterised by fever, rash, and leukocytosis. Pharyngeal exudate and the presence of heterophile antibodies are the main causative agents in the normal presentation of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) mononucleosis, which are frequently missing in CMV mononucleosis.

Anaemia, abnormal liver function tests, thrombocytopenia, positive rheumatoid factor, and elevated levels of antinuclear antibodies are some other symptoms. In immunocompetent hosts, organ involvement is rare. CMV is a significant opportunistic pathogen in patients with immune systems that are weakened, such as those who have undergone solid organ transplantation, bone marrow transplantation, or HIV treatment. This may exhibit symptoms of particular organ illnesses such hepatitis, pneumonitis, and colitis.

CMV is more aggressive in persons with weakened immune systems. the following specific disease entities:

- Fulminant liver failure that could result from CMV hepatitis

- "Pizza pie appearance" of cytomegalovirus retinitis during ocular examination

- Emphysema caused by CMV

- C. gonorrhoea from a virus

- pneumonia due to CMV

- Polyradiculopathy

- myelitis transverse

- Encephalitis subacute

EVALUATION

Rarely do patients who are immunocompetent need a firm diagnosis. On the basis of a clinical examination alone, CMV cannot be diagnosed. The preferred initial test for patients with a suspected CMV infection is laboratory viral identification. Although the finding of CMV inclusion bodies through histopathology is the gold standard for diagnosis, quantitative PCR techniques are the method of choice for viral detection. The viral load in immunocompromised people may occasionally be undetectable. A negative PCR thus does not rule out CMV infection. Before organ transplantation, serological testing is crucial for determining serostatus and risk stratification for CMV infection. It is not, however, advised for the diagnosis of an acute infection.

CMV assays are a common component of non-directed blood donor screening in many nations, despite the modest risks. Donations that test negative for CMV are reserved for patients with impaired immune systems or babies. Some blood donation facilities keep a list of donors whose blood is CMV-free for exceptional circumstances.

In transplant centres, CMV resistance testing has become widespread. Many transplant patients have ganciclovir resistance, which makes treatment challenging. Any transplant patient who fails to respond to therapeutic doses of ganciclovir or is experiencing a sharp decline in health should be suspected of having CMV resistance.

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Immunocompetent patients appear with few or no symptoms, are self-limiting, and don't need any special treatment beyond symptomatic relief. However, severe cases of CMV infection, CMV illness, and CMV mononucleosis in immunocompromised people should be taken into consideration.

Antiviral therapy does not come without risk. These agents frequently cause toxicity, thus the advantages of starting treatment must be evaluated against this risk.

Patients without CMV infection who get organ transplants from CMV-infected donors should receive prophylactic treatment with valganciclovir or ganciclovir, as well as ongoing serological testing. If treated, the early onset of a potentially fatal infection can be prevented.

DIAGNOSIS

Hepatitis virus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human herpesvirus-6, and infectious mononucleosis are the various diagnostic techniques.

PROGNOSIS

As long as they are not immunosuppressed, most CMV patients have a favourable prognosis. Treatment frequently brings recovery to an end. However, weariness could linger for a while.

If therapy is put off, CMV pneumonia in marrow transplant patients can have a significant death rate.

Since CMV can affect practically any organ in the body, a multidisciplinary approach is required. Immunocompromised patients might be given prophylactic therapy. However, one must also take drug toxicity and interactions into account. Additionally, there is always a chance of acquiring drug resistance.

Although a CMV vaccination is now being tested on transplant patients, it might take some time before it can be used on a regular basis. Long-term follow-up is required after a CMV diagnosis in an immunocompromised patient. Those who have retinitis must see an ophthalmologist for follow-up care.

CMV is rarely linked to mortality in patients who are not immune impaired. CMV, however, can cause considerable morbidity and mortality in people who are immunocompromised, cect chest receiving chemotherapy, or using corticosteroids. Mortality rates following bone marrow transplants have been reported to range from 10% to 75%. Recovery does happen for the healthy individual who has CMV, although it could take weeks or even months.

The main complaint of most survivors is still fatigue. Comorbidity and immunosuppression patients generally have a poor prognosis. Patients with CMV pneumonitis who need to be ventilated have a terrible prognosis.