In the past, less than 0.5% of patients admitted to US tuberculosis hospitals developed peritonitis, making it a rare form of the disease. The rarity of tuberculous peritonitis in North America today is illustrated by these...

Abstract

In the past, less than 0.5% of patients admitted to US tuberculosis hospitals developed peritonitis, making it a rare form of the disease. The rarity of tuberculous peritonitis in North America today is illustrated by these publications, and if previous delays in diagnosis were largely attributable to a lack of awareness of the condition's symptoms and signs, it is possible to assume that this issue will persist going forward. The discovery of additional reasons (sarcoidosis, starch, and lint) for granulomatous peritonitis as well as the issue of mycobacterial peritonitis in patients receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis has made diagnosis even more challenging.

Etymology

The phrase "peritonitis" is derived from the Greek terms "v personation" (the peritoneum, or abdominal tissue), and "-itis" (inflammation).

Epidemiology

Globally, the documented incidence of TBP among all TB subtypes ranges from 0.1% to 0.7%.17 The illness affects both sexes equally and most frequently affects patients between the ages of 35 and 45.

Worldwide TB research has employed a variety of methodologies, which could account for the disparities in the data that have been collected. Accurate estimations of the severity of this disease have become even more difficult due to rising migration as well as ongoing shifts in the disease's pattern.

Mortality statistics, tuberculin skin tests, field surveillance using chest X-rays and sputum cultures, and other techniques are some examples of ways to research TB prevalence. Due to a large percentage of vaccinated but uninfected patients reporting a positive skin reaction, BCG vaccination has reduced the value of tuberculin skin and in the analysis of TB. Similarly Because of immunization schemes implemented in the third world, obtaining useful epidemiological data on this disease by Mantoux skin testing has also become challenging.

Pathology

Most instances of tuberculosis are caused by reactivating tuberculous collections that have been dormant in the peritoneum. Dissemination via lymphatic or hematogenous channels has also been documented, in addition to direct spread from the digestive tract. It has been reported that direct extension can occur from the female genital tract.

This is how tuberculous peritonitis is typically categorized:

- Wet type

- Prevalent (90%) 1

- Type with permanent fibrosis

It is important to observe that the three types overlap significantly.

Location

Extrapulmonary TB most frequently affects the abdomen, where the peritoneal disease is the most prevalent type. In addition to the lymph glands and solid organs, the digestive system, mesentery, and abdominal tuberculosis can all be affected.

Distinct organ systems may exhibit distinct pathologies due to tuberculosis, so histopathological or laboratory evidence is frequently needed to confirm suspicions raised by imaging before starting treatment.

It's All About SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Abdominal discomfort

Acute abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness, abdominal guarding, and rigidity are the primary signs of peritonitis. These symptoms are made worse by any motion of the peritoneum, such as coughing (a forced cough may be used as a test), flexing the hips, or eliciting the Blumberg's sign. (implication that shoving a hand on the abdomen elicits minor pain than dismissing the hand abruptly, which will exacerbate the pain, as the peritoneum breezes back into place). For the diagnosis of peritonitis, rigidity has a good level of specificity (76–100%). Peritonism is the term used to describe these symptoms in an individual.

Additional signs

- Particularly in cases of generalized peritonitis, diffuse abdominal rigidity (abdominal guarding) is frequently evident.

- Sinus arrhythmia and fever

- Developing ileus paralytics, or intestinal paralysis, which also results in bloating, vertigo, and vomiting

- Reduced or absent bowel sound and abdominal gas path

Risk Elements

The following are risk factors for abdominal involvement:

Simultaneous HIV diagnosis

Dialysis in the abdomen

Cirrhosis

Whenever to visit a medical

If you don't seek therapy right away, peritonitis could be fatal. If you experience intense abdominal pain or tenderness, bloating, or a sense of fullness along with any of the following:

- Fever.

- tummy upset and vomiting.

- decreased pee.

- Thirst.

- unable to expel flatulence or stools.

- Immediately contact your healthcare

Practitioner if your peritoneal dialysis fluid:

- Ether has an odd color or are cloudy.

- Contains whitish flecks.

- Has clumps or threads in it.

- Particularly if the area around your catheter changes color or hurts, or has an odd odor.

Characteristics Of Radiography

Features of CT CT tomography associated with tuberculous peritonitis include:

- Peritoneum and mesentery swelling that is nodular or symmetrical

- Abnormal increase of the mesenteric or peritoneum

- Ascites

- Low attenuation lymphadenopathy is characterized by swollen hypodense lymph nodes.

Additionally, certain kinds of imaging can exhibit more particular features, such as:

Exudative high attenuation ascites (20–45 HU), which can be loculated or free, are considered to have a high attenuation because of their large cellular and protein content.

caseous mesenteric lymphadenopathy, fibrous adhesions, and thickened, "cake-like" omentum are characteristics of the dry variety.

Widespread peritoneal thickening on ultrasound

The parietal peritoneum often enlarges in a regular, hypoechoic fashion and occasionally displays an uneven or nodular pattern.

- Hypervascular, Frequently With Color Movement Doppler Analysis

- Ascites

- Frequently Exhibiting Intertwined Thin Fibrous Septations

- Adhesions

- Mesenteric/Omental Swelling

The appearance of the greater omentum can vary from striated to nodular to hypoechoic, with areas of alternating echogenicity.

In the early stages of the illness, there may be prominent mesenteric nodes and concurrent mesenteric thickening.

Includes the periportal, peripancreatic, and retroperitoneal nodes most frequently.

Echogenicity may be enhanced or may have a caseation-representing central hypoechoic concentration.

Pathogenesis

Peritoneal TB is believed to be caused by the reactivation of latent foci of infection that were already present in the peritoneum due to hematogenous spread from a prior pulmonary infection to the mesenteric lymph nodes. Another potential route of infection involves ingesting bacilli and then passing through Peyer's patches in the intestinal mucosa to mesenteric lymph nodes, as well as contiguous spread from infected lymph nodes or ileocecal TB. Less commonly, hematogenous spread from pulmonary disease or miliary TB, direct spread from genitourinary sites.

15 to 20 percent of individuals with abdominal TB also have active pulmonary disease. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the main causative agent, but Mycobacterium bovis has also been documented to cause abdominal TB through the consumption of unpasteurized milk.

Considering the Approach

The treatment strategy for peritonitis and peritoneal abscesses focuses on resolving the root issue, giving patients systemic antibiotics, and using supportive therapy to avoid or reduce any subsequent complications brought on by failing organ systems. Treatment success is characterized by sufficient source control, remission of sepsis, and complete clearance of any residual intra-abdominal infection.

It is essential to containing the septic source as soon as possible, and this can be done both surgically and non-surgically.

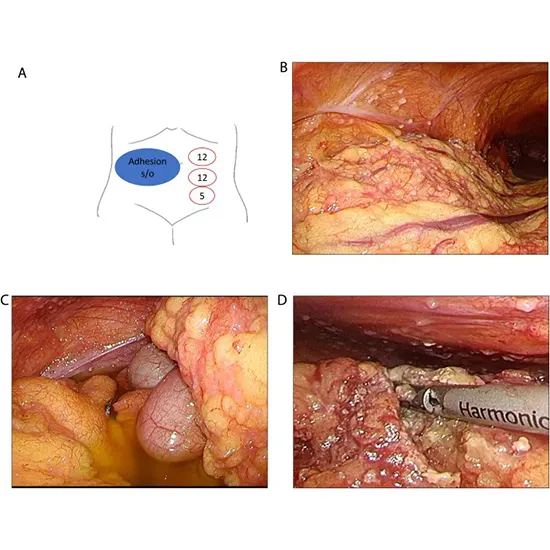

Surgical procedures

Operative management deals with the need to eliminate bacteria and toxins as well as regulate the infectious source. The underlying disease process and the seriousness of the intra-abdominal infection determine the kind and degree of surgery. The cause of the antimicrobial contamination must be eliminated, and the anatomical or functional disorder causing the infection must be corrected, to fully restore functional anatomy. Incisional surgery is used to achieve this.

On occasion, a single surgery can accomplish this; however, in some cases, a second or third operation may be necessary. In some patients, definite intervention is postponed until tissue healing is sufficient to permit a (sometimes drawn-out) procedure and the patient's state improves.

Preventing Damage While Surgery Procedures

As an alternative, over the past ten years, doctors have used damage control surgeries (DCS) to temporarily drain the infection, quickly control the visceral leak, and delay any definitive repair until the patient has stabilized. Whether the patients are hemodynamically stabilized or not, DCS seems to be an option for perforated diverticulitis, peritonitis, or septic shock.

Nonsurgical treatments

Percutaneous abscess drainage and endoscopic and percutaneous stent implantation are examples of nonoperative treatments. Percutaneous drainage is a safe and efficient first line of therapy for abscesses that are accessible for percutaneous draining and whose underlying visceral organ pathology does not call for surgical intervention. With percutaneous therapy, the meaning of success involves delaying surgery until the initial sepsis has resolved and avoiding additional operative intervention.

The basic guidelines for treating infections fall into four categories as follows:

- Infectious source management

- Get rid of toxins and germs

- keep the endocrine system working

- To reduce inflammation

Multidisciplinary medical, surgical, and nonoperative interventions are used in conjunction to address petoThe following are examples of medical support:

- Treatment With Systemic Antibiotics

- Intensive Care With Pulmonary, Kidney, And Hemodynamic Support

- Dietary Needs And Metabolic Assistance

Therapy to reduce the inflammatory reaction

Treatment for peritonitis and intra-abdominal sepsis always starts with volume reuse anotherectifyingctifanotheothers there are threessibotherepblete and coagulation abnormalities, and empiric broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotic coverage.

Antibiotic Therapy

The use of antibiotic therapy helps to decrease late complications and the local and hematogenous spread of infection. Intra-abdominal infections can be treated with a variety of various antibiotic regimens. Broad-spectrum monotherapy and combination treatments have both been applied. However, no other remedy is better than another. Anaerobes, gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, and coverage for the abdominal region are all necessary. Patients who have previously received antibiotic therapy or who have spent an important quantity of time in the hospital are instructed to obtain an antipseudomonal range.

Drainage without Operation

Evacuating a cyst is referred to as drainage. Under the direction of ultrasound or CT, this can be done surgically or subcutaneously. Simply removing the sutures or opening the wound may be adequate if the abscess is contained at the level of the skin and underlying superficial tissues. When an abscess can be fully drained and debridement and repair of the skeletal structures are not required, percutaneous techniques are favored. Diffuse peritonitis, a lack of infection localization, numerous abscesses, anatomical inaccessibility, or the requirement for surfavoredbridement are some of the factors that may make percutaneous drainage unsuccessful at controlling the cause.

The capacity to postpone surgery until the acute process and sepsis are under control and a definitive operation can be done in an elective setting is sometimes regarded as a success of nonoperative drainage.

The majority of patients with tertiary peritonitis develop complicated abscesses or badly localized peritoneal infections that cannot be drained percutaneously. Up to 90% of patients will need to have extra source control

The majority of peritonitis patients experience some form of gut dysfunction after investigation, such as ileus. Because most patients experience inadequate enteral intake for a variable period before surgery, early in the course of treatment, consider instituting some type of nutritional support. The statistics already available support the idea that enteral nutrition is preferable to parenteral hyperalimentation. Patients who are critically sick have been found to experience fewer complications when receiving enteral nutrition. Parenteral nourishment should be started if enteral feeding is unsafe or unacceptable.

Peritonitis, an infection or dehiscence at the location of the procedure, enterocutaneous fistula, abdominal compartment syndrome, and enteric deficiency are all peritonitis difficulties. The failure to use the gut for nutritional support, continuing (potentially large) volume, protein, and electrolyte losses, as well as long-term complications from intravenous alimentation can all result from enterocutaneous fistulae. A well-known illness entity called abdominal compartment syndrome is linked to numerous organ dysfunction and acutely elevated abdominal pressure (also known as intra-abdominal hypertension). Short gut, pancreatic insufficiency, or hepatic dysfunction may result from severe original (gastrointestinal) illness, chronic recurrent infections, and related reoperations.

Prevention

Peritonitis can be avoided by focusing on learned causes, the majority of which involve ingrained habits that, despite best efforts, are still difficult to control. Diverticula begin to appear in the Western populace as they get older, with an 80% prevalence in the eighth decade of life. Despite the promotion of increasing fiber and fluid intake, there is insufficient proof to back up this plan. Similar findings of prophylaxis' ambiguous efficacy plague effefiber offerention in cirrhotic patients with ascites.

Prognosis

There has been a considerable reduction in the morbidity and mortality associated with intra-abdominal sepsis over the past ten years as an outcome of enhanced antibiotic therapy, more aggressive intensive care, earlier diagnosis, and therapy using a mix of operative and percutaneous techniques.

Independent risk characteristics of the intra-abdominal view (IAV) for intense complicated intra-abdominal sepsis (SCIAS) or 30-day mortality appear to be the degree of peritonitis, diffuse substantial redness of the peritoneum, kind of exudate (fecal or bile), and a non appendiceal reason of the infection.